Schema R

Schema R is a structural diagram introduced by French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan in his 1959 essay “D’une question préliminaire à tout traitement possible de la psychose” (“On a Question Preliminary to Any Possible Treatment of Psychosis”), later collected in Écrits. It extends the earlier L-schema by integrating the register of the Real and formalizing the structural relations among the Imaginary, Symbolic, and Real in both neurosis and psychosis. Schema R plays a central role in Lacan’s theory of psychosis, foreclosure, and the symbolic function of the father.[1][2]

Historical Context

Schema R belongs to Lacan’s mid‑century effort to reformulate psychoanalysis on a structural basis, moving beyond both classical Freudian topography and ego psychology. It emerges in the context of Lacan’s engagement with psychosis and his insistence that psychic structure must be understood in terms of symbolic organization rather than developmental adaptation.

While Lacan rejected biological evolutionism and recapitulation theories, his emphasis on structural catastrophe, regression, and the return of unsymbolized material bears a distant conceptual affinity to earlier psychoanalytic attempts—most notably by Sándor Ferenczi—to think psychic life in terms of discontinuities, regressions, and catastrophic ruptures rather than linear development.[3]

Freud himself described Ferenczi’s Thalassa as "the boldest application of psychoanalysis that was ever attempted," underscoring the ambition of such structural and speculative approaches, even as later theorists—including Lacan—would rework these concerns within a linguistic and symbolic framework rather than a biological one.[4]

Structure and Description

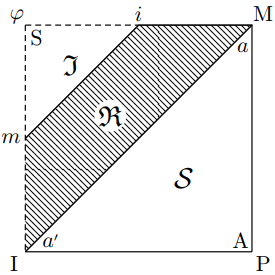

Schema R is typically presented as a quadrangular or diamond-shaped diagram composed of two interlaced triangles:

- an imaginary triangle, structuring relations of identification, rivalry, and specular misrecognition;

- a symbolic triangle, structuring kinship, law, and the Oedipal function.

Between these two triangles is situated the Real, defined by Lacan as that which resists symbolization absolutely.

The schema thus articulates how:

- the Imaginary organizes ego relations,

- the Symbolic organizes subjectivity through language and law,

- the Real marks a point of impossibility, rupture, or structural limit.

Function of the Real

In Schema R, the Real is not conceived as a primitive biological substrate or evolutionary residue, but as a structural remainder—that which cannot be integrated into the symbolic network. This distinguishes Lacan’s position sharply from earlier psychoanalytic models that grounded regression or catastrophe in phylogenesis or organic memory, such as those proposed by Ferenczi or influenced by Lamarckian and recapitulation theories.[5]

Nevertheless, the thematic concern with repetition, regression, and catastrophic return persists in transformed form: in Lacan, what “returns” in psychosis is not a biological past but a foreclosed signifier returning in the Real.

Schema R and Psychosis

Schema R is central to Lacan’s structural account of psychosis. In psychosis, the Name‑of‑the‑Father is foreclosed (forclusion) from the symbolic order. As a result:

- the symbolic triangle fails to stabilize subjectivity,

- the Real intrudes directly into experience,

- imaginary constructions (delusions, hallucinations) attempt to compensate for symbolic failure.

Schema R allows this process to be mapped formally, showing how disruption at the symbolic level produces effects in both the imaginary and the Real.[6]

Relation to Other Lacanian Schemas

- L-schema – Schema R expands the L-schema by incorporating the Real and Oedipal structure.

- Schema I – A deformation of Schema R representing psychotic structure after foreclosure.

- Graph of Desire – Later formalization introducing temporality and signifier chains.

- Borromean knot – A topological model replacing schematic diagrams with knot theory.

Schema R marks a transitional moment between Lacan’s early schematic models and his later topological formalism.

See also

References

- ↑ Lacan, Jacques (2006). Écrits. Translated by Fink, Bruce. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-32925-2.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ↑ Evans, Dylan (1996). An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis. Routledge. ISBN 9780415132881.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ↑ Ferenczi, Sándor (1938). Thalassa: A Theory of Genitality. W. W. Norton & Company.

- ↑ Freud, Sigmund (1933). New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis. Hogarth Press.

- ↑ Abraham, Nicolas (1962). Rythmes: De l’œuvre, de la traduction et de la psychanalyse. Aubier.

- ↑ Lacan, Jacques (1993). Miller, Jacques-Alain (ed.). The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book III: The Psychoses, 1955–1956. W. W. Norton & Company.